Becoming an Effective Coach for Law Students

The students are at different stages of development on both of the two foundational learning outcomes above and the two student goals of bar passage and meaningful post-graduation employment. An effective curriculum has to go where each student is developmentally and engage at the student’s current developmental stage; this is why individualized one-on-one coaching is so powerful.

An effective coach with these goals is offering individualized guided reflection and guided self-assessment to foster each student’s growth. What are the most important capacities and skills for an effective coach? A reader who wants a twenty-page overview of the scholarly literature on effective coaching should look at The Foundational Skill of Reflection in the Formation of a Professional Identity by Neil Hamilton, available at the SSRN website.

The next dropdown summarizes the most important capacities and skills needed by a coach for law students.

An effective coach offers individualized guided reflection and guided self-assessment to foster each student’s growth.

A reader who wants a twenty-page overview of the scholarly literature on effective coaching should look at Mentor/Coach: The Most Effective Curriculum to Foster Each Student's Professional Development and Formation by Neil Hamilton, available at the SSRN website.

There is empirical evidence that a forty-five-to-sixty-minute coaching interview to promote student reflection with respect to self-directed learning is effective and can have an important and lasting impact on a student.[1]

For example, a study of 102 undergraduates (with a mean age of twenty-one) involved a trained interviewer conducting a one-on-one, in-person interview designed to promote reflection about the student’s purpose in life, core values, and most important life goals. The study included both a pretest and a posttest nine months later, for assessing the impact of the interview.[2] On average, the coaching engagement led to benefits for student goal-directedness toward life purpose nine months later.[3] The authors suggest that these conversations are “a triggering event [that] would impel an emerging adult, who is likely in this stage of life to be predisposed to identity exploration, to reflect on life beyond the interview in considering his or her life path.”[4] In general, individualizing students’ learning experiences, so that the students can practice versus just observe, and combining these individualized experiences with an instructor who provides continuous feedback to the students have been associated with more learning benefits than large-group training with respect to self-directed learning.[5]

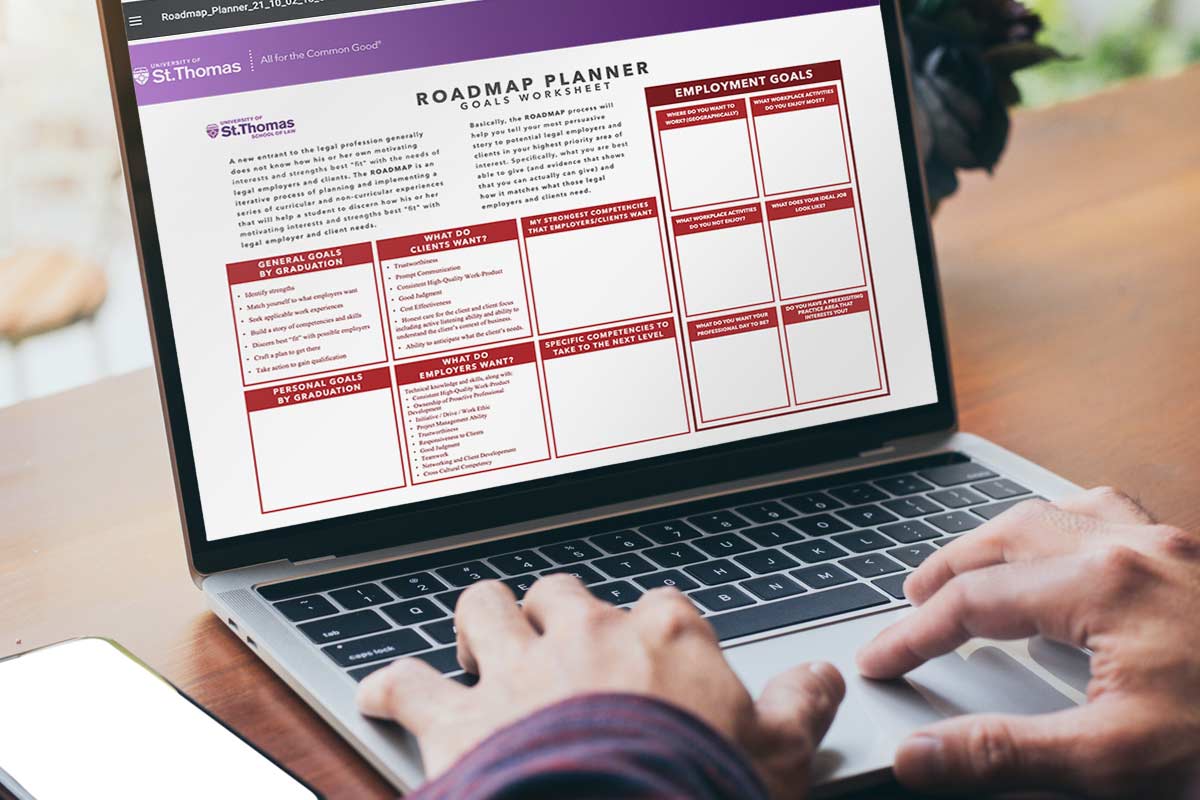

We recommend the coaching guide below that we provide to our coaches at the University of St. Thomas School of Law who are coaching 1L students in January and February of the spring semester on each student’s written plan to use the student’s remaining semesters of law school most effectively to achieve the student’s goals of bar passage and meaningful post-graduation employment. The guide gives good examples of powerful, open questions to foster each student’s guided reflection and self-assessment.

A reader who wants to focus on growing to the next level with respect to active listening skills should look at Teaching and Assessing Active Listening as a Foundational Skill for Lawyers as Leaders, Counselors, Negotiators, and Advocates by Lindsey Gustafson, Aric Short, & Neil Hamilton, available at the SSRN website.

Footnotes

[1] Matthew J. Bundick, The Benefits of Reflecting on and Discussing Purpose in Life in Emerging Adulthood, 132 New Directions Youth Dev. 89, 93 (2011).

[2] Id. at 93.

[3] Id. at 97–98.

[4] Id. at 98.

[5] Ryan Brydges et al., Self-Regulated Learning in Simulation-Based Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, 49 Med. Educ. 368, 369–70, 372, 374 (2015).