The 2015 winner of the E. Smythe Gambrell Professionalism Award from the American Bar Association, Professor Neil Hamilton has developed and published a groundbreaking template for law students to use throughout all three years of law school to be fully prepared to find meaningful employment upon graduation.

“Every student desires meaningful employment to serve others well upon graduation,” Hamilton writes. The most effective way for a law student to gain meaningful employment, he notes, is to first understand the student’s own strengths; second, to understand the competencies desired by employers; and third, to discern how the student’s strengths met those desired competencies.

The Roadmap, therefore, has established the core competencies desired by law firms, corporate legal departments, and governmental law departments, to demonstrate what competencies each student should be developing in his/her formative law school years. Through a combination of one-on-one coaching and student-driven growth plans, each student identifies specific competencies and career goals, and then demonstrates progress over their remaining semesters of law school.

Contact

Neil Hamilton

3rd Edition of Roadmap Now Available

Purchase the Book

Third Edition Supplemental Materials

Chapter 1 - Table 4

Ask Person A and ideally a second person, Person B, who know your earlier work/service well to rank your top four strengths in terms of the capacities and skills that clients and legal employers want in the context of your previous work/service with customers/persons served including work on teams.

Assessment of ________________________ (student name)

Capacities and Skills - Rank the Student’s Top Four in Order (1-4)

- Superior focus and responsiveness to the customer/persons serve

- Exceptional understanding of the context and business of the customer/persons serve

- Effective communication skills, including listening and knowing your audience

- Creative problem-solving and good professional judgment

- Ownership over continuous professional development (taking initiative) of all of the capacities and skills needed to serve well

- Teamwork and collaboration

- Strong work ethic

- Conscientiousness and attention to detail

- Grit and resilience

- Organization and management of the work (project management)

- An entrepreneurial mindset to serve customers/persons served more effectively and efficiently in

changing markets

Chapter 2 - On-line Template

Roadmap Template

Name of Student: _________________________

Please read Chapter 1 first. You may need to refer back to Chapter 1 for longer descriptions of some of the steps in this template.

This template focuses on your plan to gain a breadth of experiences during your remaining time in law school so that you can:

- thoughtfully discern your passion, motivating interests, and strengths that best fit with a geographic community of practice, a practice area and type of client, and type of employer;

- develop your strengths to the next level; and

- have evidence of your strengths that employers value.

If you already have post-graduation employment, fill out the Roadmap template with an eye toward your capacities and skills that will most benefit your employer and its clients. What experiences will help you develop those capacities and skills to the next level? Show your plan to experienced lawyers at your future employer and ask for feedback. Reflect on the feedback.

Fill in the template with reasonably brief answers. You can use bullet points. Remember that the coaches who will help you with feedback will only have time to read reasonably brief answers. Include your resume when you send this template to a coach for feedback.

Chapter 5 - On-line Template

On-Line Template for Building a Tent of Professional Relationships Who Both Support You and Trust You to Do the Work of a Lawyer

Intro (download full template below):

Please read Chapter 4 first. You may need to refer back to Chapter 4 for longer descriptions of some of the steps in this template.

This template focuses on building a tent of professional relationships who both support you and trust you to do the work of a lawyer. Steps 1-4 emphasize specific professional relationships you should be building in the 1L year. Step 5 involves professional relationships with practicing lawyers and judges who have observed your work and trust you to do the work of a lawyer. Step 6 asks you to build a professional relationship with one or more mentor/coaches. Some 1L students may already have these Step 5 and Step 6 professional relationships, but many students will be building these Step 5 and Step 6 professional relationships in the summers between the 1L and 2L year and the 2L and 3L year, plus other experiences mimicking the actual work of a lawyer during the 2L and 3L years. Step 7 addresses expanding your tent of professional relationship beyond those covered in Steps 1-6. A student in any year of law school can be developing professional relationships with practicing lawyers and judges at law school or bar association events.

Remember that in any time period, you are “leaning” your professional-relationship-tent-building efforts to help you with experiences that will test your fit with your answers to Step 5 of the Roadmap template regarding your fit with a geographic area, an area of practice/type of client, and type of employer.

Fill in the template with reasonably brief answers. You can use bullet points. Remember that a coach who will help you with feedback will only have time to read reasonably brief answers.

Resources

Introduction

It is true that taking pro-active ownership of your professional development at the beginning of your professional career falls on your shoulders, but during your time in law school, you have many resources at your disposal. The Roadmap process encourages you to seek feedback and input from mentors and coaches on your initial drafts of the Roadmap Template and your written networking plan, and at each transition point throughout law school.

Visit Your School’s Office Dedicated to Career and Professional Development

Connecting the dots among your newly created Roadmap plan, your networking plan, and the rest of your law school’s available resources is vital. Once you have completed your plan, it is very important to sit down with a representative from your school’s office for career and professional development to discuss your plans and get their feedback on the plans. They also can help you so that your persuasive communication package, which includes your résumé, your cover letter, your interview strategy, and your references, is effective with your target audience of potential employers. For example, they can help you with mock interviews. You should see your school's office for career and professional development each semester and develop a strong relationship with them.

How to Navigate Resources for Researching Potential Employers

Research by Type of EmployerStudents who want to research potential employers by type of legal employer (e.g., large firm, small firm, county attorney, etc.) can begin researching their most promising employment options by accessing the University of St. Thomas School of Law research guide on career and professional development resources available at http://libguides.stthomas.edu/law_student_career_resources. If that link doesn't work, the guide is available through the following steps: Go to the University of St. Thomas School of Law page. In the top right-hand corner, select the link for “Law Library.” Once in the law library website, under “Research Resources,” select the link for “Research Guides.” Once on this page, select the link “here” within the sentence, “The legal subject area libguides can be found here.” The research guides are organized alphabetically. Scroll down to the letter “C” and select the link for “Career and Professional Development Resources for Law Students.”

|

Large Firms |

Martindale-Hubbell Law Firm Practice Yale Law School Guide: Law Firm Practice |

|

Solo or Small-Firm |

Yale Law School Guide: Law Firm Practice |

|

County Attorney |

Yale Law School Guide: Criminal Prosecution Yale Law School Guide: Public Defender PSJD: Careers in Criminal Law |

|

Attorney General |

Yale Law School Guide: Public Interest Careers |

|

Alternative Legal Employment Options |

Yale Law School Guide: Lawyers in Business Jonathan C. Lipson, Beth Engel, Jami Crespo, Foreword: Who’s in the House? The Changing Nature and Role of In-House and General Counsel, 2012 Wis. L. Rev. 237 (2012). |

Research by Practice Area

Students who want to research their most promising employment options by practice area should start by going to the University of St. Thomas School of Law page. At the top of the page, select the link for “Tools.” This will bring up a drop-down menu. In the drop-down menu, select the link for “Libraries.” Once in the library website, select the link at the top-left of the page titled “Research & Course Guides.” This will bring up an alphabetical list of subjects for which librarians have created research guides. Click on “Law” to reveal a variety of law practice areas.

|

General (All Careers) |

NALP Student Resources ABA Career Paths From Georgetown Law Library: Job Searching Research Guide Yale Law School Guide: Career Guides PSJD: Career Options |

Employment and Volunteer Opportunities While in Law School

Students can then use the resources listed in Parts 2 and 3 below to begin seeking out employment and volunteer opportunities to gain experience at their most promising employment options to further test whether their options are the best fit for them. Additionally, students should use their networking plans to start building long-term relationships with these employers and conduct informational interviews with attorneys to further refine their most promising employment options. Note that students do not need to find an explicit job posting. Students should also seek out an area of employment that interests them and make a connection with that employer—unpaid positions are not always posted or advertised. Students should make themselves available to gain experience by taking initiative and offering to help employers in creative ways.

|

General (All Careers) Experience |

Association of Corporate Counsel Yale Law School Guide: Career Topics Additional Resources: · Indeed |

|

Social Justice Experience |

Advocates for Human Rights: Opportunities for volunteering, internships, and fellowships on issues such as international relations, refugee and immigration reform, death penalty activism and global gender violence. American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU): Careers, fellowships and legal internships aimed at expanding civil liberties and civil rights across the United States. 180 Degrees, Inc.: local volunteer opportunities with high-need clients in Minnesota on criminal and social justice issues. Council on Crime and Justice: Site for information and policy change on issues of criminal and social justice, with the option to develop your own volunteer position. |

|

Local and State Government Experience |

PSJD: Public service employment opportunities, searchable by city and state. (Federal and State) |

|

Federal Government Experience |

USAJobs: Search federal jobs by profession and location U.S. Department of Justice (Intern): Every year over 1,800 volunteer legal interns serve in DOJ and U.S. Attorneys’ Offices throughout the country. Approximately 800 legal interns volunteer during the academic year, and roughly 1000 volunteer during the summer. You can also search for Fellowships. |

|

Nonprofit Experience |

Center for Constitutional Rights: Jobs, internships and fellowship opportunities. CCR is a non-profit legal and educational organization committed to the creative use of law as a positive force for social change. Homeline: Tenant advocacy internships providing extensive training on Minnesota tenant-landlord law from expert attorneys, providing legal advice to tenants, and working with local policymakers. Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota: Volunteer and internship opportunities in immigration law include language translation, legal assistance, and research. National Legal Aid & Defender Association: Job board that typically posts positions in civil legal aid, defender organizations, pro bono and public interest organizations, public interest law firms, and academia. Volunteer Match: General legal volunteer opportunities ACLU of Minnesota: Volunteer opportunities with the Minnesota chapter of the ACLU |

Neil Hamilton, Shana Tomenes, Rob Maloney, Carl Numrich, and Davis Cheney contributed to this section.

Framework for 20-Minute Informational Interviews

The following discussion is largely a synthesis of The 20-Minute Networking Meeting.[1]

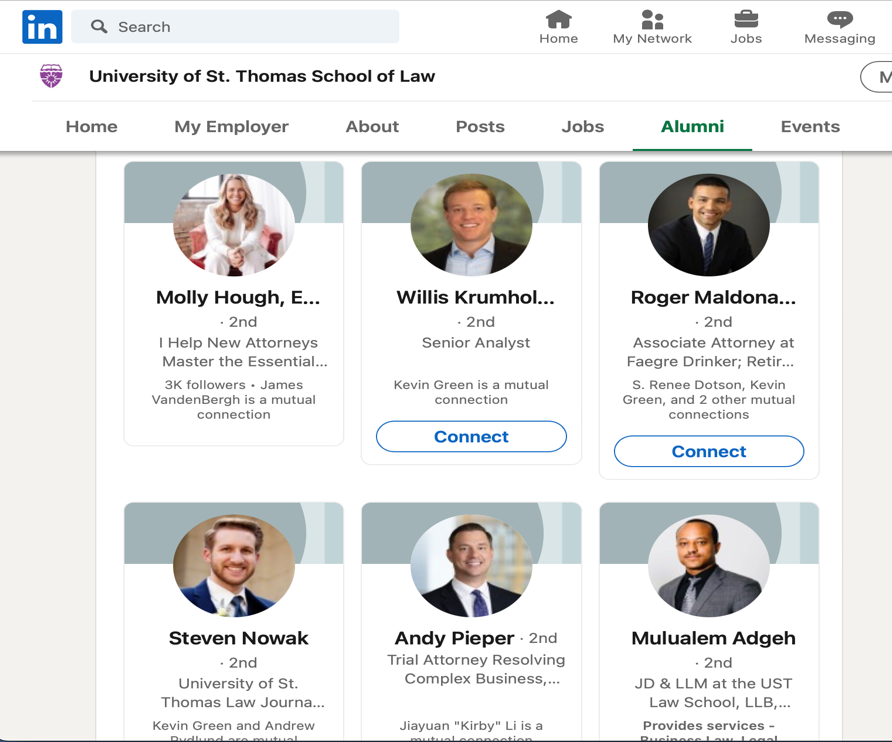

Initiating the Relationship

If you discover a potential contact through your efforts outlined in Chapter 4, it is a valuable use of time to determine whether you have any other contacts in common with that person who are able to provide you with an introduction or referral to the potential contact. The potential contact is more likely to be willing to meet with you if you know people in his or her tent of professional relationships. If you use LinkedIn to research your prospective contact, you may discover that you have a contact in common with your prospective contact of which you were not aware. Even if you do not have any contacts in common with the potential contact, it is still appropriate for you to initiate a meeting, but it may be more difficult to get the potential contact to find time for you. However, don’t let this discourage you from trying to connect with a potential contact!

When initially contacting a professional to set up an informational meeting, it is often helpful to use both e-mail and phone because the professional may prefer one method of communication over the other. Regardless of how you contact the professional, the message should include information regarding who you are, your connection with the professional, and a specific question relevant to the professional’s expertise that you wish to discuss with the professional (your prior research on the professional is essential here).[2] In addition, your message should be error-free, maintain a professional tone, and express gratitude for the professional’s time. If you do not receive an immediate response to your initial contact, do not be concerned. It is generally appropriate to contact the professional again in one or two weeks.[3] If the professional is too busy or otherwise unable to meet with you presently, you may ask whether you may contact her in a month or two to attempt to set up an informational meeting at that time. If the professional agrees, be sure to contact her within the stated time.

The Meeting

Once you have successfully set up a time to meet, you need to prepare to run a meeting that will leave a positive impression on the professional. The 20-Minute Networking Meeting offers an excellent structure of how to effectively direct an informational meeting and make the greatest positive impression on a contact by outlining the meeting into four categories: (1) the first impression, (2) the overview, (3) the discussion, and (4) the ending.[4]

The suggestions below on how much time to spend in a given portion of the meeting are flexible, but you should aim to spend only about 20 minutes in an informational meeting.[5] If the meeting is going very well and your contact is directing the conversation to last longer (or if the meeting is for lunch) you can allow the meeting to run longer, but you need to do your best to take only as much time as you requested from your contact. Because you are forming a lasting relationship, you will have more chances to talk with the professional. Better to leave the professional wanting more than less.

i. The First Impression

You only get one chance to make a good first impression. Arrive to the meeting several minutes early knowing where you are meeting, how to get there and where to park. You should also have the professional’s phone number on hand in case you run into an unavoidable delay. If you are meeting at the professional’s office, do not check in more than 10 to 15 minutes early because the professional may feel unnecessarily rushed or uncomfortable having you wait. If you arrive too early, find a place to wait where you can review the questions you wish to discuss. Remember that you begin making first impressions the moment you arrive, so be respectful and courteous to everyone you meet. If you do not act professionally toward support staff, word will get back to your contact and likely damage the otherwise positive impression you made.

Once you are in the meeting with the contact, remember to run it efficiently. Twenty minutes is sufficient to establish a positive connection, engage in a thoughtful discussion, and show consideration for the professional’s time by not using more of it than is necessary. You should use a couple of minutes to establish a connection with the professional and make a good first impression by being confident, positive, and professional (and make sure you know how to pronounce the contact’s name).[6] This includes expressing gratitude for her or his time, highlighting your mutual connections, and giving a summary of what you wish to discuss with the contact.[7] Throughout the meeting, you should make good eye contact and use active listening skills —show the professional that you enjoy listening to her. You should also bring a pad and pen to write down notes for the follow-up.

ii. The Overview

Next, take one minute to provide a brief overview of your educational and work experiences and career interests.[8] Yes, this is a short amount of time to cover everything you’ve done, but this is an informational meeting, not a job interview. Use your value proposition for a couple of your strongest competencies. What do you most want the person to remember about you? You do not want to bog down the contact with all of the little details of your background; rather, you want to give enough information to provide a general sense of your background while being efficient with your use of the contact’s time. Try to consider two strengths that will help your target audience of top employment options that you want them to remember about you.

iii. The Discussion

Following the summary of what you wish to discuss and your background, you should spend about 12 to 15 minutes engaging the professional in a thoughtful discussion.[9] This is where your research about the professional and the firm or company is essential. You should prepare several questions, which are both specific and relevant to the contact’s experience.[10] A good way to format such questions (and display the effort you put into researching and preparing for the meeting) is to pair an observation that you gained through your research of the contact with a relevant question to that observation.[11] For example, a question may be phrased: “I see that you work in your firm’s energy regulation department. What steps should I be taking while in law school to gain experience in this area of law?” Leading with an observation provides the contact with a “heads-up” regarding the topic of your question and will help you ask a question that is specific to her or his experiences and expertise.[12]

After several questions specific to the professional’s areas of expertise, you should also ask if she has any referrals for you to contact in your relationship building endeavors. Although it may feel forward to request contacts from the professional you are meeting, this is a generally accepted practice and is of vital importance to expanding your network in an intentional and effective manner. There are several reasons not to avoid this question: your contact understands the value of networking; your contact agreed to meet with you and is likely expecting you to request additional names; your contact may have come prepared with names for you; and your contact may not give you the names unless you request them.[13] In addition, most job offers are not the result of relationship building with one’s original contacts but, rather, result from networking to the “Third Ring” of contacts (i.e., contacts of contacts of contacts). An informational meeting that is conducted in a professional, well-organized, and thoughtful manner is likely to inspire the professional’s trust, which may mean she is more willing to give you contacts because she has reason to believe that you will conduct yourself in a similar manner with any contacts provided.[14] This question will yield the best results if it is phrased specifically, as opposed to one broadly phrased: “Do you know anyone I could contact?” If your contact does not have any names with which to provide you, simply thank them graciously and proceed to the final question of the meeting.[15]

The final question recommended by The 20-Minute Networking Meeting is to ask your contact, “How can I help you?”[16] This question reflects the reciprocal nature of relationship building and also displays thoughtfulness and gratitude for the time and knowledge that the professional has shared with you (think about it: if the attorney you meet with bills at $250/hour, your 20-minute meeting was an $83.33 gift).[17] Although the question from The 20-Minute Networking Meeting is intended to be asked by business executives, law students should also seriously consider ways in which they may be able to assist a contact.[18] For instance, if the contact heads a professional or charitable association, bar section, or a similar organization (information you can gather through your prior research on the contact), you may volunteer for or offer to promote upcoming events.[19]

Asking the question “How can I help you?” will only be effective if it is genuine and sincere.[20] Even if you are currently unable to help the professional as a student, a sincere offer of future assistance will leave the professional with a positive final impression of you as a thoughtful and considerate person (i.e., the type of person that everyone likes to know and help when possible).[21] Finally, and most importantly, you should focus on following through with any advice and referrals that the professional provides and updating the professional when you do follow through with the advice and referrals, because the professional intrinsically benefits from the personal satisfaction of helping you to grow professionally.[22]

iv. The Ending

The final step of the meeting is to take two minutes to express your gratitude for the professional’s time, advice, and assistance. Review any action you promised to take on her behalf, such as forwarding a scholarly article that might be helpful in her research, and thank your contact for any actions she will take on your behalf, such as providing you with another’s contact information.[23] Thank the professional again for her time as you leave. If you met in the professional’s office, be sure to thank the assistant or any other helpful staff. Very often the assistant has a close relationship with the professional and the professional will take into serious consideration the assistant’s impression of you. Also, many times it will be easier for you to contact the professional in the future if you know her assistant’s name and contact information, because the assistant often sets the professional’s schedule and may have a better idea of when the professional is available than the professional does. You want to exit the meeting leaving a positive final impression on everyone because information will travel back to your contact if your behavior is less than professional. Be sure to stick the landing.

[1] See generally NATHAN PEREZ & MARICA BALLINGER, THE 20-MINUTE NETWORKING MEETNG (2016).

[2] See Networking, U. ST. THOMAS CAREER & PROF'L DEV. (March 22, 2023), https://www.stthomas.edu/career-development/resources/networking/

[3] Id.

[4] See perez & ballinger, supra note 1, at 65.

[5] Id. at 58

[6] Id. at 66.

[7] Id. at 68.

[8] Id. at 75.

[9] PEREZ & Ballinger, supra note 1, at 81.

[10] Id. at 90.

[11] Id. at 91.

[12] Id.

[13] Id. at 93

[14] Id. at 94.

[15] Id. at 97.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Networking, supra note 2, at “Step 4.”

[19] Id. at “Step 7.”

[20] PEREZ & Ballinger, supra note 1, at 98.

[21] Id. at 99.

[22] See id. at 104.

[23] Id. at 104-05.

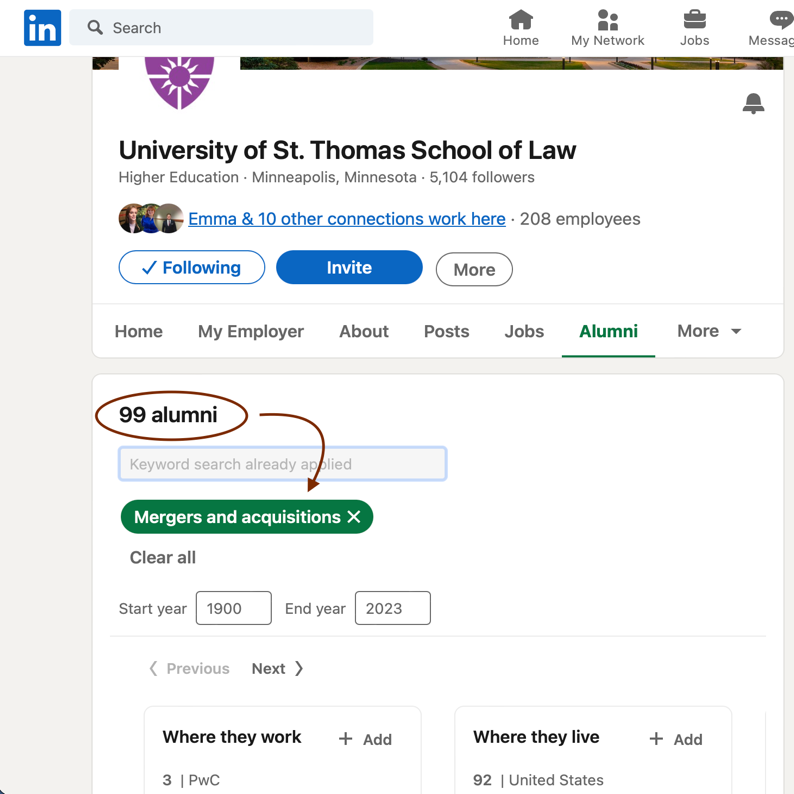

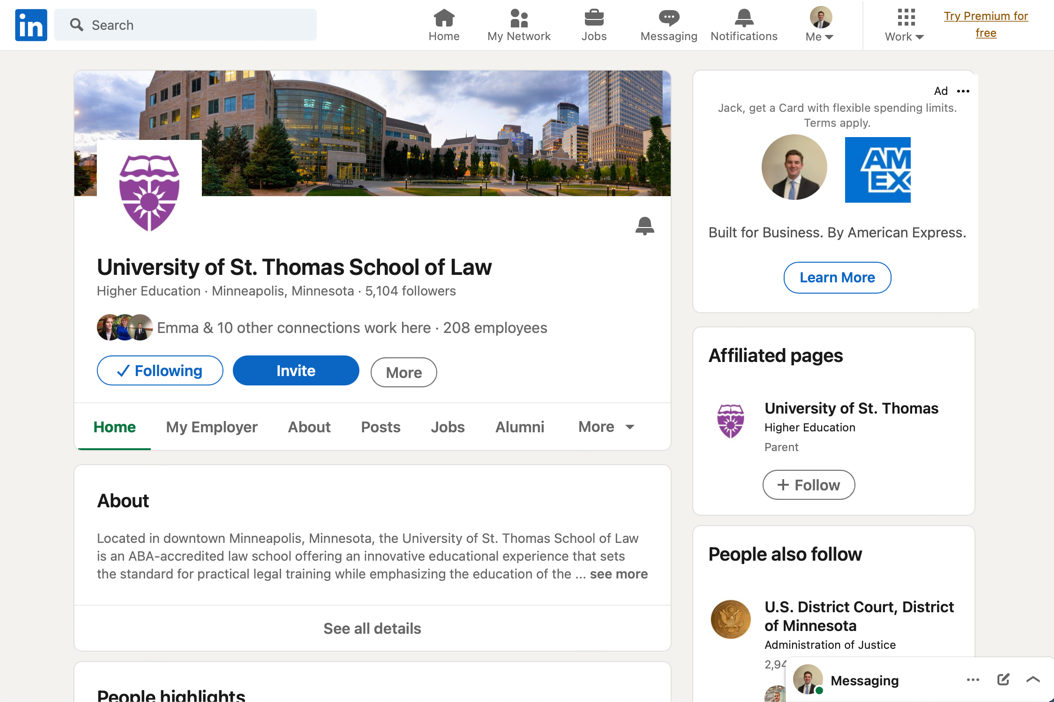

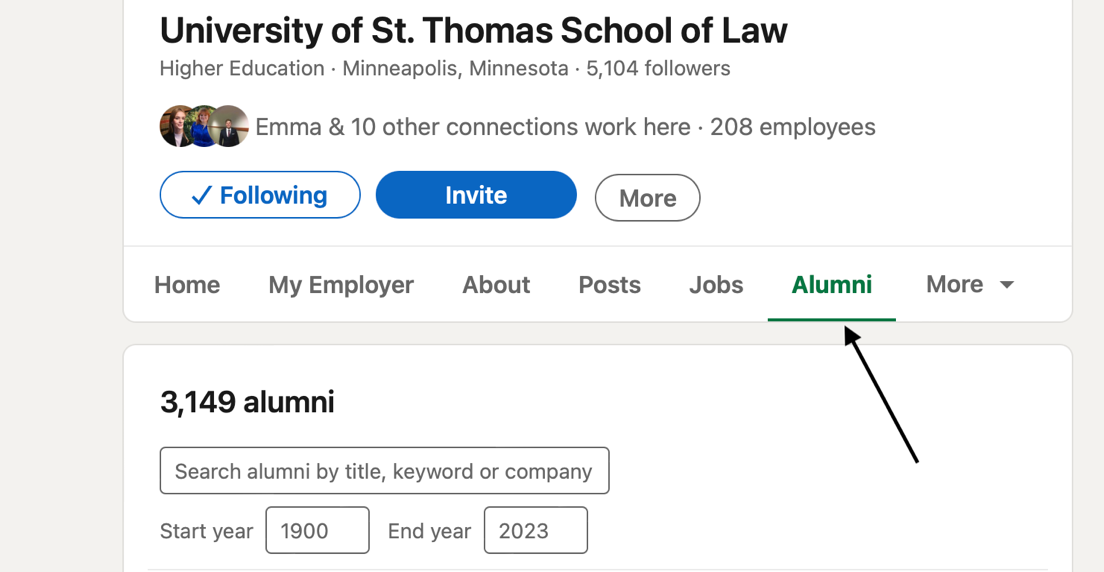

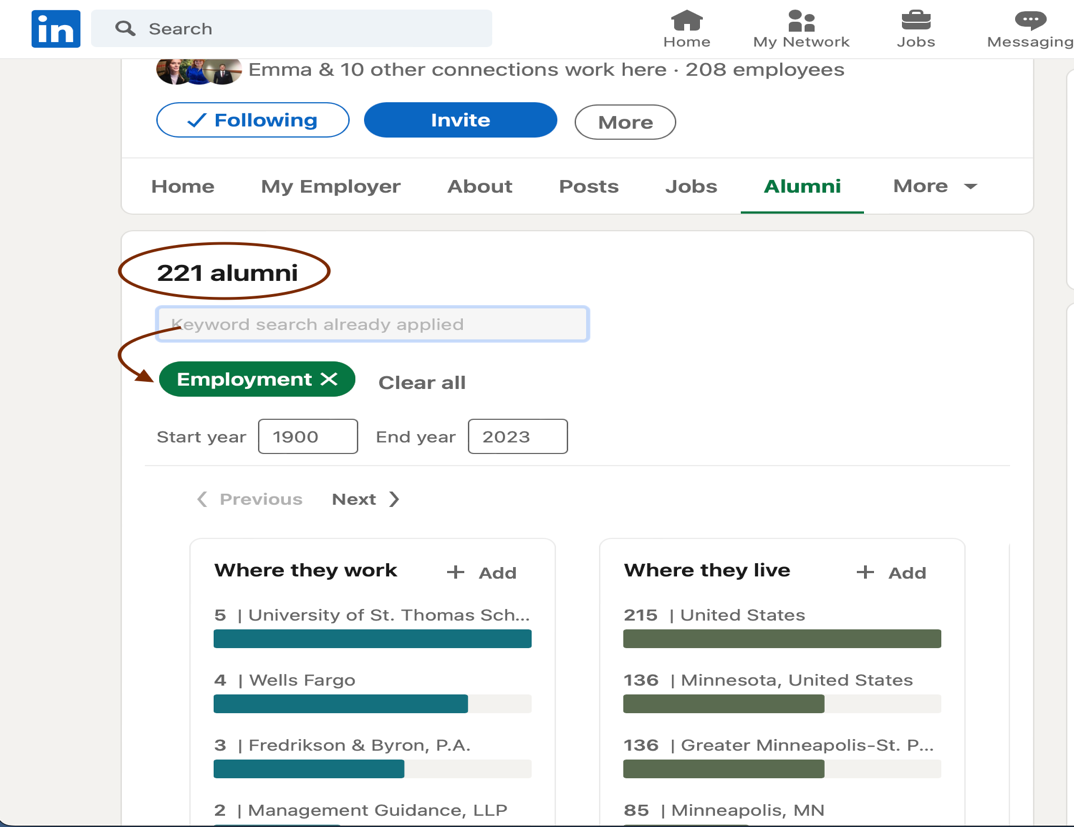

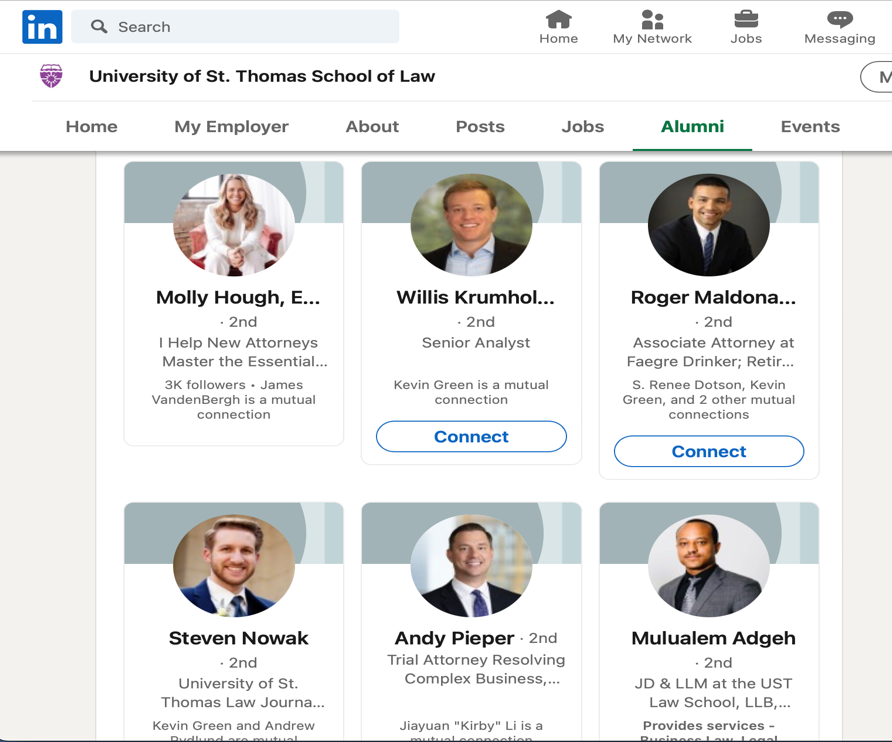

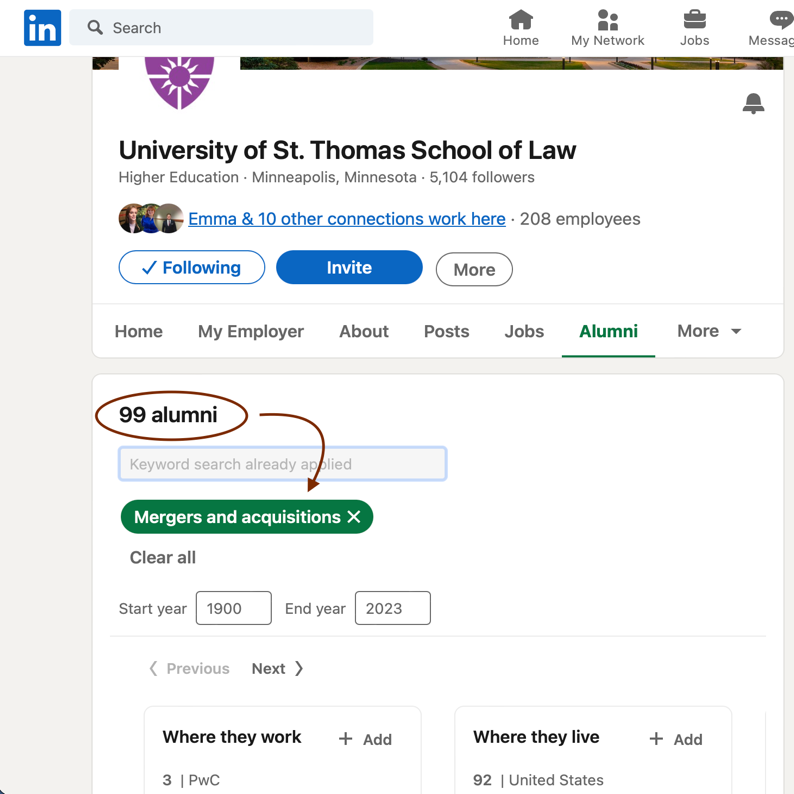

Steps for LinkedIn Searches

The steps below use the University of St. Thomas School of Law as an example. Substitute your own law school or undergraduate school and follow the same steps.

- Navigate to LinkedIn and search “University of St. Thomas School of Law.”

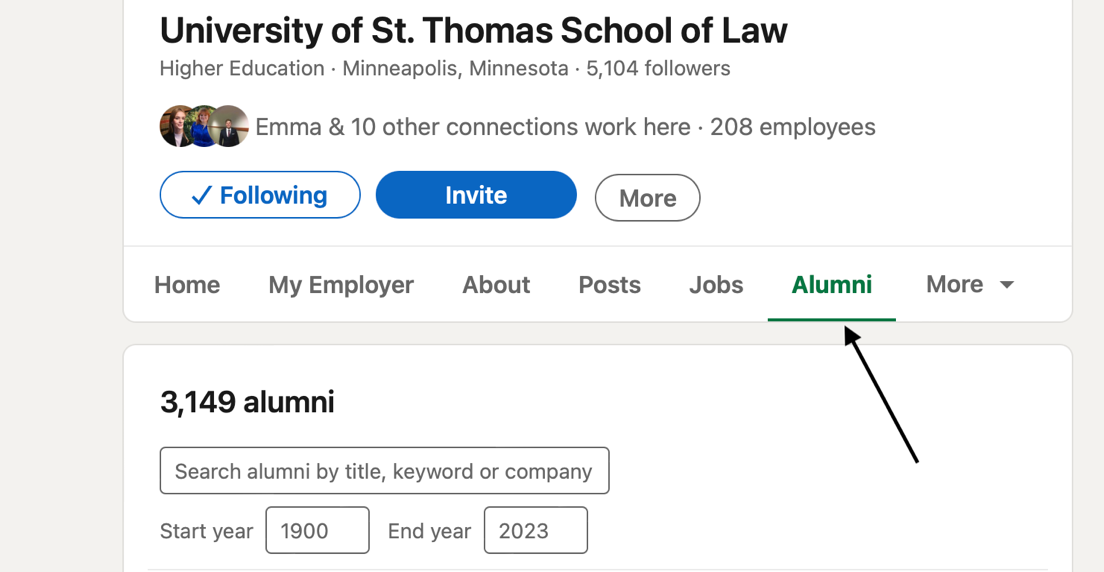

- Click “Alumni.”

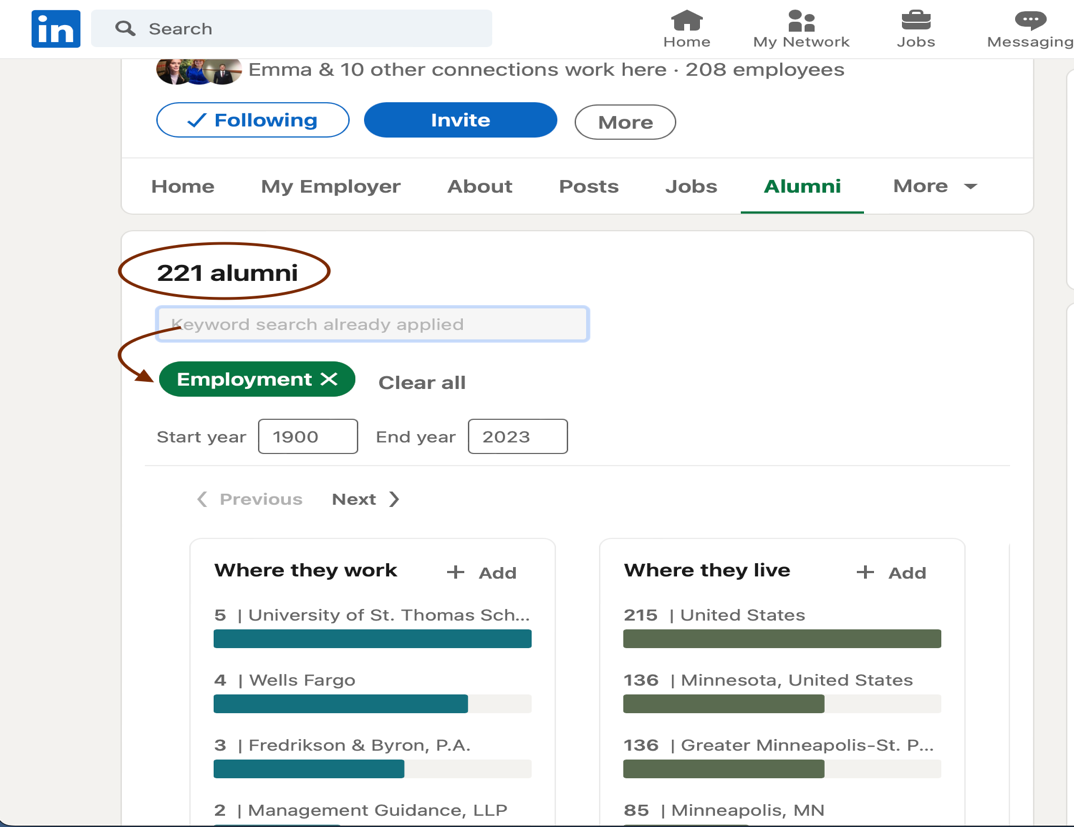

- In the Search Bar, search a practice area. Here, I searched “Employment” to find attorneys who specialize in employment law. As shown below, the search yields the number of attorneys who practice employment law, where they work, and where they live.

If you continue to scroll down, LinkedIn will provide attorneys who graduated from St. Thomas School of Law and who have “Employment” in their biography.

- However, this search is not completely accurate (as shown below). LinkedIn yielded different results when I searched “mergers and acquisitions” versus “M&A.” So, it is important to be thorough when searching for areas of law because LinkedIn will only produce results if the attorney has that exact word or wording in their profile.

Jack Golbranson provided the research on these steps.

Building Relationships with Experienced Lawyers

This memo is written by Annie Boeckers in 2021 after her 2L-3L summer working for a large firm in Minneapolis. She now is an associate at that firm. The letter outlines a few tips and tricks that helped her navigate both her projects and working relationships with experienced attorneys giving her work.

- Overall Goal – Making Your “Client’s” Job Easier

As a student attorney, your job, fundamentally, is to make the assigning attorney’s job easier. The assigning attorney is essentially your “client.” Your assigning attorneys know the law. And they know how to find the answers they’re asking you to look for. You are there to save them time. A partner or senior associate may not have three hours to dig into the case law for one legal issue on a case – but a student attorney does. Your effort reading through the case law, forming a legal conclusion, and succinctly explaining your conclusion to the partner (both orally and in writing) allows the partner to move forward on the project without investing hours of their time. This summer, I spent over seven hours researching and briefing an issue for a supervising attorney. My research was boiled down to a 20-minute phone call where the partner presented our conclusions to the client. - Understand the “Deliverable”

However, you cannot make your supervisor’s job easier if you do not give them exactly what they want. And giving them exactly what they want requires you to fully understand what they are expecting. Your first task on any project, even before you start researching or writing, is to figure out what the attorney wants the final work product to look like. To make sure I understood each project and the attorney’s expectations, I kept a notepad next to my computer with questions to ask my assigning attorneys in every initial project meeting. I made sure to cover everything on the list before the end of the meeting. I’ve attached the list here:

- What specific work product are you looking for – a memo, an email, a draft letter?

- How much time should I spend on this project?

- Is the time limit set by the client (do not exceed), or is the timeframe an estimate for how long you think it should take me to complete the project?

- What client/matter number should I bill my time to?

- How should I describe this project on a bill? Is there specific language I should use? Is there specific language I should NOT use?

- What’s a good place to start my research?

- When is the due date? (Once you have the exact date, clarify if the attorney wants your work product by end-of-day, noon, or beginning of day – you’d be surprised!)

- What’s the best way to communicate with you if I have any questions – email, text, phone, etc.?

Even if you think you know the answers to some of these questions, ask anyway. You will work for attorneys who want everything sent in an e-mail even if you send the equivalent of a five- page memo. You will work for attorneys who want everything in a memo format even if it could have been a five-sentence e-mail. You will work for attorneys who prefer to communicate via e- mail and others who prefer phone calls, text messages, or computer IM’s.

Some attorneys will say to never use the word “research” on a bill to the client, even if all you did was Westlaw research. They will tell you to write, “analyze case law on [insert legal issue].” In my experience, attorneys are happy to answer these questions at the outset and are impressed that you thought to ask. It saves the partner time and makes their job easier – which is your most important job!

- Navigating Uncertainty by Demonstrating Progress

It is almost inevitable that questions will come up as you work on the project. That is expected. When you start to have questions, first ask yourself whether these issues are so central to the project that you cannot continue working unless they are resolved. If you are able to continue working on other aspects of the project, get as far as you can before going back to the assigning attorney. Keep track of your questions and progress so you can circle back later. There may even be people around you other than the assigning attorney that can answer your questions. In fact, the assigning attorney should be your last resource for asking questions. Your legal administrative assistant, if you have one, is an excellent resource. Your fellow student attorneys are also a great resource. If there is another junior attorney on the project with you, try asking them. If you do have to go back to the assigning attorney, make sure you are as far along on the project as you can be without having your questions answered.

If you have a research project that doesn’t lead you anywhere (which is way more common than you would think), the answer you give an assigning attorney should never be just “no,” or “I couldn’t find anything.” Here’s a sample email I once sent to an assigning attorney for a dead-end research project:

“Dear Attorney X,

I hope you are well. I looked at the case law on [insert legal question] and was unable to find any cases that said exactly [A]. However, I found a few cases that said [B] and a few cases that said [C]. Would you like me to continue looking into [B] or [C]? Or would you like to set up a meeting to discuss next steps?

-Annie”

It’s best practice to give them an idea of what you did find, even if it’s not exactly what they wanted you to find. What you found might still be helpful. Sometimes the answer really is “no, there’s nothing out there” but it’s better for the attorney to make that call after you’ve presented them with what you found.

- Drafting with “Attorney’s Voice”

If you have projects that require you to draft anything in a supervising attorney’s name (a letter to a client, a motion to dismiss, a request for documents, etc.) take a few extra minutes before you start writing to look over something the assigning attorney previously wrote. Ideally, if you’re drafting a motion to dismiss, try to review a prior motion to dismiss drafted by the supervising attorney. But even if it’s not the same kind of document, you can pick up on important details that help you create a document the partner doesn’t need to spend time re-writing.

For example, my first writing assignment was to draft a demand for restitution letter on behalf of the assigning attorney. I couldn’t find any prior demand letters the attorney had completed, but I read through one of their most recent briefs. I noticed right away the attorney used two spaces after each sentence. I also paid attention to the writing style, sentence structure, and any particular vocabulary. I would never use the word “aforementioned” in my own work, but my assigning attorney used it twice in the brief I read, so I used it in the letter. Of course, the attorney made changes to my draft, but minor edits take way less time than re-writing the entire document. - Managing Feedback – Growth Mindset

Even when you ask all the right questions and go into projects fully prepared to do a great job, you will have to manage constructive feedback. For every project I completed, the assigning attorney filled out a project evaluation form that prompted them to answer questions on my legal analysis, legal writing, communication skills, professionalism, whether my work product met their expectations, etc. The last question on the evaluation form asked the attorney to provide the summer associate with one perceived strength and one piece of constructive feedback. During my mid-summer and end-of-summer evaluations, I found that the summer hiring committee was less concerned about what the constructive feedback was, and more concerned with how I responded. With all feedback, I found it best to be gracious about it, acknowledge that you understand why you received the feedback, and share what you learned and how you’re going to improve on the next project.

Receiving any kind of constructive feedback can be difficult, but you may also receive feedback that you don’t find helpful. For example, I submitted a research memo for an assigning attorney that I thought was one of my best projects all summer. The assigning attorney liked it too and gave such great feedback on the research and writing that I decided to submit the memo as one of my two writing samples for the summer. The feedback I got on the writing sample from a blind-reviewer was overwhelmingly negative. You would have thought I’d never written a memo before! I ended up going through all the comments and corrections and sorted them into three categories, 1) helpful for this project, 2) not helpful for this project but may be helpful for a future project, and 3) not helpful. See examples below:

- Helpful for this project: “this sentence fits better later in the paragraph.” This is a standard organizational tip.

- Not helpful for this project but may be helpful for a future project: “you talk about this Rule of Evidence but never explain what it is or why it matters.” I understood why the blind-reviewer wrote that on my memo and reading it from their perspective I realize why they asked for that level of detail. However, the assigning attorney for the research memo didn’t need me to explain what the Rules of Evidence are – that was not the point of the research memo. In fact, explaining what the Rules of Evidence are to an attorney who practices white collar crime seems quite silly. So, for purposes of submitting a research memo to the assigning attorney, this kind of comment is not as helpful. But, for future memos (especially ones with blind audiences that have little context of the larger project), I’ll remember to write with greater detail and provide further explanations when needed.

- Not helpful: The reviewer added very obscure Latin words and phrases that I had never heard of and had no idea what they meant. While some people prefer to use this kind of language in their writing, I do not, and I will not be incorporating that feedback into future projects.

To be clear, categorizing the feedback like this was something I did privately and on my own time. As law students and young lawyers, it is best to outwardly treat all feedback as helpful feedback. In my evaluation, I accepted all the feedback on my writing sample and talked about how each comment and suggestion will improve my legal writing moving forward.

Best Blogs

A great source for topics of interest to lawyers and judges is legal blogs. There is a plethora of legal blogs that touch on various aspects of the law.

To give one example of how reading a blog could lead to a good conversation, you can assume that practicing lawyers and judges are interested in general in the topic of changing markets for legal services. They will be interested in the impact of technology on the practice of law and the profession. Assume you have spent 15 minutes reading several recent blog postings in the blog Legal Evolution or Law21 about a predicted change in the market for legal services. You could say in any conversation with practicing lawyers that “I just read a post on _____________. Is this what you are seeing?”

Another approach is to ask if the lawyer has been reading recently about the changing markets for legal services. Then subsequently, ask if anything is of particular interest to them and why. Further, a great question for practicing lawyers is– what you are reading to stay up to date on changing markets for legal services.

The first list below contains the three highest trafficked legal blogs that are pertinent to the field of law. The second list contains a group of useful blogs on changing markets for legal services. The third list has other helpful blogs in the social justice or government practice areas.

HIGHEST TRAFFIC LEGAL BLOGS:

Above the Law: Above the Law is a legal web site providing news, insights, and opinions on Law firms, Lawyers, Law school, Law suits, Judges and Courts. It takes a behind-the-scenes look at the world of law. The site provides news about the profession's most colorful personalities and powerful institutions, as well as original commentary on the latest legal developments.

ABA Journal Magazine | The Lawyer's Magazine: Get continuous news updates from the United States' most-read and most-respected legal affairs magazine and website, ABA Journal. It is the flagship magazine of the American Bar Association, covering the trends, people and finances of the legal profession from Wall Street to Main Street to Pennsylvania Avenue.

Lawyerist.com: Lawyerist is home to the largest online community of solo and small-firm lawyers in the world. Their goal is to help lawyers build better law practices by bringing together a group of innovative lawyers to share ideas, experiments, and best practices.

BLOGS ON CHANGING MARKETS FOR LEGAL SERVICES:

Law.com - The American Lawyer: This is the website for the magazine “The American Lawyer”, they have been in publication since 1979. They are a good source for information about the legal industry.Adam Smith: This blog is on the economics of the legal services industry.

Legal Evolution - Bill Henderson: This is curated by a team, and there are regular posts with great insight on the industry, but it is inactive for some months in 2023.

Law Sites: This website keeps track of new tech innovations and startups in the legal field to better stay up-to-date on cutting edge changes.

Law21 - Jordan Furlong: This is Jordan Furlong’s blog where he gives his insight into the changing legal landscape.

OTHER HELPFUL BLOGS:

Social Justice:

The Nation: The Nation focuses on recent social justice developments. It provides “spirited debate about politics, social justice, equality, and culture. Further “The Nation empowers readers to fight for justice and equality for all.

The Conversation: The Conversation offers informed commentary and debate on the issues affecting our world.

Government Jobs:

Government Jobs Blog: Government Jobs Blog is a very useful networking tool for law students intending to work for the government. Some of the various topics the blog covers, inter alia, are: (1) government interview and resume tips; (2) an overview of government employment; and (3) government employment statistics.

Davis Cheney helped update this Appendix.

Developing Cross Cultural Competency

Developing Cross-Cultural Competency for the Changing Workplace[1]

No matter a lawyer’s practice area, it is extremely important that each lawyer possess the ability to interact and communicate effectively with people from other cultures. Cargill general counsel Laura Witte emphasizes “To be truly effective counselors in today’s global marketplace, it is not enough to know the law. We must be able to communicate, build relationships, interpret and apply the law in the context of applicable cultural norms, norms that may be very different from our own.”[2] In a litigation context, law professor Susan Bryan urges that “[l]lawyers who explicitly examine the cross-cultural issues in a case will increase client trust, improve communication, and enhance problem-solving on behalf of clients.”[3] As several scholars have noted, “in today’s multicultural world, students must develop into culturally sensitive lawyers who understand how their own cultural experiences affect their legal analysis, behaviors, and perceptions.”[4] It is strongly in a lawyer’s self-interest to develop cross-cultural competence in his or her everyday work.

Cross-cultural competence can be broadly defined as the ability to “effectively connect with people who are different from us — not only based on our similarities, but also with respect to differences.”[5] Accordingly, it is necessary for a lawyer to first identify the various cultures to which he or she belongs in order to understand which cultures are different than the lawyer’s own. Indeed, “[a] broad definition of culture recognizes that no two people have had the exact same experiences and thus, no two people will interpret or predict [culture] in precisely the same way.”[6]

Culture is defined in this context as “the body of customary beliefs, social forms and material traits constituting a distinct tradition of a racial, religious or social group.”[7] Culture, for example, can include a person’s age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or physical ability. Even if the lawyer shares all of those categories with the other person, different regions of the same country may have different cultures. Different organizations may also have different cultures.

For a lawyer to truly provide competent representation to his or her clients, the lawyer must not only understand the law, but also understand the culture of the client, of the teams and other groups with whom the lawyer works to advance the client’s interests, and of adversaries and decision-makers whom the lawyer seeks to influence. Without awareness of the various cultures of these stakeholders in a lawyer’s work, a lawyer cannot see how culture affects the representation. For example, not considering a client’s culture could cause a misunderstanding of the client’s goals, needs, and personal preferences. If a lawyer chooses to ignore the cultural differences between the lawyer and his or her clients, it is likely that the representation will not be as effective as it should be. The inability to understand a client’s culture can also make it more difficult for the lawyer to build trust in the relationship.[8]

Beyond the client context, attorneys also encounter many different cultures when interacting with coworkers, other firms, opposing counsel, judges, support staff, etc. It is equally as important to be cognizant of how different cultures affect the lawyer’s encounters with these individuals. Failing to recognize how different cultures may affect these interactions can lead to confusion, misunderstanding, and even broken relationships. In contrast, cross-cultural competence improves trust, communication, and problem-solving among both peers and clients, while also acknowledging the inherent dignity of each person.

In our view, empathy is at the heart of developing cross-cultural competency. Empathy is an ability to understand the other’s experiences and perspectives combined with an ability to communicate this understanding and an intention to help. In simpler terms, empathy is the ability to walk in another person’s shoes, to view life from his or her perspective, and to communicate that understanding and an intention to help.

This Appendix will establish that cross-cultural competency is an affirmative competency that both law students and legal practitioners can develop throughout their careers. Further, this Appendix will also show that it is in the law student and legal practitioner’s enlightened self-interest to become culturally competent. With practice, the legal practitioner can come to identify and understand when his or her cultural lens, biases, and stereotypes are affecting the relationship with clients and others. Through this affirmative approach, legal practitioners can better and more effectively serve their clients and ensure a result that best suits the client’s needs. Finally, this chapter will give practical advice and techniques as to how the law student and lawyer can begin to improve his or her cross-cultural competence.

- The Effects of Cross-Cultural “Incompetence”

A good starting point for a discussion on why it is important to develop cross-cultural competence is to examine first the negative effects of being cross-culturally “incompetent”. One of the most common reasons a lawyer is culturally incompetent is because the lawyer fails to recognize that a need for cultural competence exists in the situation. Susan Sample better illustrates this point:

Cultural differences can be easy to miss . . . It is particularly important for professionals because they very well may be the person with the highest status in the room, and people with higher status do not necessarily have a lot of experience at looking for cultural differences and adapting to them. For example, if a person is U.S. American, or male, or upper middle class, or European American, or any combination of those things, they may not recognize all the cultural differences in the room because they are inadvertently making everyone conform to them, and thus, their cultural norms.[9]

It is in instances like the one above where problems arise as a direct result of a lack of cultural awareness and competency.

One major problem that a culturally incompetent attorney may encounter is the difficulty establishing trust in the attorney-client relationship.[10] Without trust, a relationship between the lawyer and client cannot work well. Trust is not established simply because the client chose the lawyer to represent him; rather the lawyer must work to establish trust in the relationship.[11] Being culturally competent can help the lawyer to accurately understand their client’s goals and behavior and use this information to create a trusting relationship.

A culturally incompetent attorney will also likely miss important information because of failed or misunderstood communication.[12] In particular, because we interpret our surroundings and encounters through our own lens, there may be a gap between our own understanding and another person’s understanding.[13] When the lawyer interprets the client’s messages through his or her own lens, communication can easily break down. As a result of the lawyer’s failure to recognize the inherent differences and nuances of each culture, he or she may make decisions that the client may not have chosen. Communication failures can have a detrimental effect on the attorney-client relationship. In fact, “[s]studies show that client satisfaction often relates as much to how lawyers communicate as to actual results achieved in a given case. Effective lawyers must be able to recognize, and appropriately respond to, their own and others’ cultural perceptions and beliefs because these often play a central role in lawyer-client communications.”[14]

Last, cultural incompetence “may impede lawyers’ abilities to effectively interview, investigate, counsel, negotiate, litigate, and resolve conflicts.”[15] Not recognizing the impact that culture plays on a lawyer’s interactions with another can lead the lawyer to ask the wrong questions, suggest an unfavorable course of action, take a bad settlement offer, or even lead to an inability to resolve a conflict.

- Developmental Stages

Many scholars have attempted to classify the various “stages” that a person may fit into on a spectrum of cross-cultural competence. While not every model can perfectly describe the nuances of the process of developing cross-cultural competence, the models do provide useful guideposts that allow a person to self-reflect and gauge where he or she may fall on the spectrum. While we do not view any one of these models as “best” or “complete”, each model we have chosen to discuss below are all representative, relatable, and applicable to the process of developing cross-cultural competence.

When reading through the descriptions and examining the charts for each of the models, the law student or lawyer should complete a self-assessment (accessible electronically at [insert link]) and estimate his or her developmental stage. Once he or she has this self-assessment, we suggest taking these grids and asking at least two others—who have previously observed him or her working in a cross-cultural context—to assess the law student or the lawyer using the same assessment. By completing both the self and peer assessment, the reader will have an indication of how others perceive his or her cross-cultural abilities which in turn gives the law student and lawyer a basis to self-reflect on cross-cultural aptitude. From there, the law student and lawyer can use the information gathered to find areas for improvement and to develop a plan to enhance their cultural competence.

a. Milton Bennett’s Model of Cross-Cultural Competence

Dr. Milton Bennett created one of the most notable and widely-used cultural competency models, called the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) in Table 1 below. Within Bennett’s model, the underlying assumption is that cross-cultural competency can be developed over a period of time as a person continues to experience more culturally diverse situations.[16] The DMIS is made up of six stages: three ethno-centric stages where one experiences his or her own culture as “central to reality”, and three ethno-relative stages where one experiences his or her own culture as relative to other cultures.[17]

Table 1: Milton Bennett’s Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity[18]

|

Stage |

Description |

Examples |

|

|

Ethno-centric Stages |

(1) Denial of Difference |

People in this stage are in denial about cultural difference and cannot differentiate culture as a category. They have an inability to perceive or construe data from differing cultural contexts. |

“As long as we all speak the same language, there’s no problem.” “With my experience, I can be successful in any culture without any special effort—I never experience culture shock.” |

|

(2) Defense Against Difference |

People in this stage tend to experience culture as “us vs. them.” They generally feel threatened by those that are different. Generally, they exalt their own culture and degrade the other’s with negative stereotypes. |

“Why don’t these people speak my language?” “When I go to other cultures, I realize how much better my own culture is.” |

|

|

(3) Minimization of Difference |

People in this stage recognize cultural differences, but over-emphasize human similarity and universal values. As a result, they tend to believe that it is sufficient to “just be yourself” in cross-cultural situations. |

“Customs differ, of course, but when you really get to know them, they’re pretty much like us.” “If people are really honest, they’ll recognize that some values are universal.” |

|

|

Ethno-relative Stages |

(4) Acceptance of Difference |

People in this stage accept all values, behaviors, and cultures. They recognize the alternatives to their culture. Acceptance does not mean agreement with alternative values or cultures. |

“Sometimes it’s confusing, knowing that values are different in various cultures and wanting to be respectful, but still wanting to maintain my own core values.” “The more difference the better – it’s boring if everyone is the same” |

|

(5) Adaptation to Difference |

People in this stage apply their acceptance of difference and recognize the need to interact effectively with people from other cultures. They act in culturally appropriate ways in different cultural contexts. |

“I know they’re really trying hard to adapt to my style, so it’s fair that I try to meet them halfway.” “To solve this dispute, I’m going to have to change my approach” |

|

|

(6) Integration of Difference |

People in this stage are no longer defined by any one culture but are often multi-cultural. They have made a sustained effort to becoming competent in a variety of cultures. |

“Whatever the situation, I can usually look at it from a variety of cultural points of view.” “Everywhere is home, if you know enough about how things work there.” |

Bennett’s three ethno-centric stages include denial, defense, and minimization.[19] Denial is the stage in which a person does not recognize any cultural differences and believes his or her culture is “correct”.[20] Next, a person in the defense stage recognizes that other cultures exist, but does not acknowledge that these other cultures are valid.[21] Third, those in the minimization stage tend to overemphasize the universality of their cultural and minimize the actual differences between different cultures.[22]

People in an ethno-relative stage are considered to have developed more cultural competency than those in an ethno-centric stage. The first ethno-relative stage in Bennett’s model is acceptance. A person in this stage recognizes and views other cultures as valid and sees their culture as just one option among many. Generally, people at this stage tend to be accepting of cultural differences.[23] The second stage is adaptation. This stage is one in which people view cultural differences as a good thing and try to consciously adapt to the cultural norms of the surrounding environment.[24] The last stage is integration. At this stage a person does not feel that he or she belongs to any specific culture, but rather can adapt and shift between various cultures and Worldview.[25] The integration stage however is not per se better than the adaptation stage, rather it describes the cultural integration process experienced by “many members of non-dominant cultures, long-term expatriates, and ‘global nomads.’”[26]

b. William Howell’s Model of Cross-Cultural Competence

William Howell developed another model of cross-cultural competence. [27] This model is less detailed than Bennett’s and is generally applied within the context of students. This particular model consists of four stages: (1) unconscious incompetence; (2) conscious incompetence; (3) conscious competence; and (4) unconscious competence.[28] Each stage is discussed in Table 2 below.

Table 2: William Howell’s Model of Cross-cultural Competence

|

Stage |

Name |

Description |

|

1 |

Unconscious Incompetence[29] |

Characterized by a student’s total lack of awareness of the impact of culture and a failure to recognize cultural differences |

|

2 |

Conscious Incompetence[30] |

A student is aware of the role that culture plays in his or her interactions with others, but does not possess the skills needed for competent, cross-cultural interactions with others. |

|

3 |

Conscious Competence[31] |

A student possesses the skills necessary to effectively communicate across cultures, but must consciously recognize and implement these skills in his or her cultural interactions |

|

4 |

Unconscious Competence[32] |

A student is able to unconsciously implement and use his or her cross-cultural competency skills in all of the student’s interactions with others |

c. Model of Cross-Cultural Competency Borrowed From the American Board of Internal Medicine

We borrowed from the American Board of Internal Medicine’s (ABIM) Milestone Project that defined the key competencies for internal medicine residents and stages of development of each competency. This project defined developmental stages of “Responding to Each Patient’s Unique Characteristics” and “Professional and Responsible Interaction with Others.” Tables 3 and 4 show both of these stage development grids adapted for the practice of law.

Table 3: Developmental Stages in Responding to Each Client’s Unique Characteristics and Needs (Adapted from the ABIM Model Applicable to Residents)

|

Responds to each client’s unique characteristics and needs. |

||||

|

Critical Deficiencies |

Early Learner |

Advancing Improvement |

Ready for unsupervised practice |

Aspirational |

|

Is insensitive to differences related to culture, ethnicity, gender, race, age, and religion in the client/lawyer encounter Is unwilling to modify representation to account for a client’s unique characteristics and needs |

Is sensitive to and has basic awareness of differences related to culture, ethnicity, gender, race, age and religion in the client/lawyer encounter Requires assistance to modify representation to account for a client’s unique characteristics and needs |

Seeks to fully understand each client’s unique characteristics and needs based upon culture, ethnicity, gender, religion, and personal preference Modifies plan to account for a client’s unique characteristics and needs with partial success |

recognizes and accounts for the unique characteristics and needs of the client Appropriately modifies representation to account for a client’s unique characteristics and needs Recognizes and accounts for the unique characteristics and needs of the client Appropriately modifies representation to account for a client’s unique characteristics and needs |

Role models professional interactions to negotiate differences related to a client’s unique characteristics or needs Role models consistent respect for client’s unique characteristics and needs |

Table 4: Developmental Stages in Professional and Responsible Interaction with Others (Adapted from the ABIM Model Applicable to Residents)

|

Has professional and respectful interactions with clients and members of the inter-professional team (e.g. peers, ancillary professionals and support personnel). |

||||

|

Critical Deficiencies |

Early Learner |

Advancing Improvement |

Ready for unsupervised practice |

Aspirational |

|

Lacks empathy and compassion for client and the team Disrespectful in interactions with client and members of the inter-professional team Sacrifices client needs in favor of own self-interest Blatantly disregards respect for clients privacy and autonomy |

Inconsistently demonstrates empathy, compassion and respect for clients and the team Inconsistently demonstrates responsiveness to client’s and the team’s needs in an appropriate fashion Inconsistently considers client privacy and autonomy |

Consistently respectful in interactions with clients and members of the inter-professional team, even in challenging situations Is available and responsive to needs and concerns of clients and members of the inter-professional team to ensure strong representation Emphasizes client privacy and autonomy in all interactions |

Demonstrates empathy, compassion and respect to clients and the team in all situations Anticipates, advocates for, and proactively works to meet the needs of clients and the team Demonstrates a responsiveness to client needs that supersedes self-interest Positively acknowledges input of members of the inter-professional team and incorporates that input into plan as appropriate |

Role models compassion, empathy and respect for client and the team Role models appropriate anticipation and advocacy for client and team needs Fosters collegiality that promotes a high-functioning inter-professional team Teaches others regarding maintaining patient privacy and respecting client autonomy |

d. The Roadmap’s Model of Cross-Cultural Competency

We borrowed from the Bennett, Howell, and internal medicine models to synthesize our own developmental model of cross-cultural competency in an attempt to define stages of cross-cultural competency where a student or practitioner could demonstrate affirmative evidence of the competency. The Roadmap model in Table 5 also recognizes that it is possible to be at a later stage of cross-cultural competence in a particular area, like gender, while also being at an earlier stage in another area like age or race.

There are four stages to the Roadmap development model of cross-cultural competency: (1) lack of awareness; (2) recognition; (3) conscious implementation; and (4) proficiency. A person in the first stage, lack of awareness, does not recognize that he or she lacks cross-cultural competency. Someone in this stage may stereotype people in other cultures or feel uncomfortable interacting with others that are different from them. In general, this stage reflects ignorance of the role that culture plays in his or her life.

At the second stage, recognition, a person acknowledges a lack of cross-cultural competency, but may be unsure of how to develop this skill. A person may notice the role that culture plays and reflect on how his or her culture affects decisions. At this stage a person begins to see the need to develop cross-cultural competency.

At the third stage, conscious implementation, a person takes affirmative steps to develop cross-cultural competency by engaging in self-reflection and refraining from making on-the-spot judgments in unfamiliar situations. In addition, the person is open to culturally diverse experiences. While there may be some difficulty or discomfort in these interactions, the person reflects on the difficulties and discomfort and seeks greater understanding. It is the affirmative steps taken to become more cross-culturally competent by a person in this stage that are important.

At the final stage, proficiency, a person has become educated about a particular culture and could be considered “cross-culturally competent” in that area. A person at this stage is able to interact freely and genuinely within another culture and understands the differing viewpoints and customs of that culture. Interactions with those who belong to the other culture reasonably approximate those with someone from the person’s own culture. There is a genuine respect and appreciation for the other culture, although this need not be marked by agreement with it.

Table 5: The Roadmap’s Developmental Model of Cross-Cultural Competency

|

Stage |

Description |

Affirmative Evidence |

Examples |

|

(1) Lack of Awareness |

People in this stage are entirely unaware of their insensitivity to other cultures around them; they cannot comprehend the importance of becoming cross-cultural competent or what it even means. |

Accepts one’s own beliefs as superior to others Negatively stereotypes others who are different from themselves Refuses to interact with others who are different or in culturally diverse social situations |

Accepts one’s own beliefs as superior to others Negatively stereotypes others who are different from themselves Refuses to interact with others who are different or in culturally diverse social situations |

|

(2) Recognition |

People in this stage recognize that they lack cultural competence, but are unsure how to develop this into an affirmative skill; they begin to recognize the importance of understanding and accepting other cultures. |

Sees the wide variety of cultural diversity around oneself Recognizes the need to be able to interact with anyone in any situation Begins to seek out information on how to develop cultural competency |

“I wish I could speak another language.” “I think studying abroad would give me a different perspective on the world.” “I always go to lunch with the guys and need to try other groups too.” |

|

(3) Conscious Implementation |

People in this stage begin to take affirmative steps in developing their cross-cultural competency; they now place themselves into cultural situations that they would not have before. |

Places him or herself in culturally diverse situations Researches and learns more about other cultures Begins to break-down previously held stereotypes of different cultures. |

“I should try to remember that everyone has differing opinions that they all deserve my understanding and respect.” “Even though I might not agree, I can see why they think that way.” |

|

(4) Proficiency |

People in this stage take affirmative steps on a regular basis to understand others and ensure cross-cultural competence; they recognize and account for the unique characteristics and needs of others. |

Experience with working in multi-cultural team on projects Continuing/strong relationships with people from other cultures Experience living in cultures very different than one’s own culture |

“It is important to look at the situation from someone else’s shoes.” “We need to understand and respect others’ differences to work together most effectively.” |

- Developing Cross-Cultural Competence

Inherent in each of the above models is the idea that a person is able to develop skills to become more cross-culturally competent and grow in understanding through the several stages. This idea, however, raises the question: what are the most effective strategies to become more cross-culturally competent? While there is no clear-cut answer to this question, there are many pathways for a person to become more culturally aware and to develop the skills needed to become cross-culturally competent.

One of the most important pathways to become cross-culturally competent is through careful observation. Observation is the basis for recognizing differences and the beginning to an understanding of another culture’s norms, traditions, and behaviors. It is important to ask, “‘what is going on here that I do not understand?’ It must be a constant question in a person's mind.”[33] Without first observing and understanding the cultures around us, it is unlikely that a person can become culturally competent.

Hand-in-hand with the need to observe is the need for self-reflection. What types of reflection then, are most helpful? As Bryant notes, “[e]effective cross-cultural interaction depends on the lawyer's capacity to self-monitor his or her interactions in order to compensate for bias or stereotyped thinking and to learn from mistakes.”[34] First and foremost then, self-reflection includes identifying a person’s own culture, stereotypes, and biases. Through this process of self-reflection, a person can observe other cultures and identify the similarities and differences between different cultures. Moreover, this process of comparative reflection will promote an understanding of misperceptions of others and how different cultures may clash.

Empathy was defined earlier as an ability to understand others’ experiences and perspectives combined with an ability to communicate this understanding and an intention to help. Being empathetic thus requires that a person puts themselves into another’s shoes in order to feel what it is like to be that person.[35] An important part of walking in another person’s shoes involves looking at their perspective in an unbiased and neutral manner — viewing their situation in this way can help further understanding of another’s behavior.[36] An empathetic Worldview also focuses on similarities people share rather than differences. A focus on similarities, bypassing the superficial differences, acknowledges the basic humanity of each person.[37]

Empathy is demonstrated by active listening.[38] According to Hamilton, “effective listening requires not only technical proficiency, but also an empathic ability to connect with the speaker.”[39] For the lawyer to be an effective, empathic listener then, it is best he or she uses active listening techniques because it allows the lawyer to show clients that he or she understands them.[40] Moreover, active listening allows the lawyer to orientate “the conversation to the client's world, the client's understandings, the client's priorities, and the client's narrative.”[41] Through this focus on the client, the lawyer is able to gather culture-sensitive information and then use that information to ensure respect for the client’s culture and wishes.[42] This process of gathering and using culture-specific information helps the lawyer to develop his or her cross-cultural competency capacity and to retain culture-specific information to guide conduct in similar situations in the future. Taken as a whole, the habits of observing, listening, self-monitoring, and undertaking self-reflection will help develop empathy.

Each law student and lawyer must practice cross-cultural competency in order to improve. Indeed, “like the learning of other lawyering skills, learning cross-cultural lawyering skills occurs through incremental learning and by practice . . .”[43] Like all other learned skills in your life, becoming cross-culturally competent is not something that will be automatic or easy; rather, it is a career-long endeavor that requires patience and diligence. Through the course of this conscious implementation process, a lawyer will still certainly encounter difficult or uncomfortable cultural situations. In these types of cross-cultural situations where a person is unsure what to do, an effective strategy is to “simply ask others about their perspective or even their feelings regarding a specific situation or occurrence.”[44] By asking someone to clarify when the lawyer or law student is unsure, he or she ensures respect for the other’s cultural practices. Overall, addressing these new and uncomfortable situations prevents miscommunication and helps the lawyer develop the knowledge of how he or she can approach a similar situation in the future.

- Conclusion

There is no doubt that today’s world is increasingly multi-cultural. Now, more than ever, it is important that law students and lawyers alike develop cross-cultural competency and understand how culture affects their everyday practice of the law. As noted at the outset of this chapter, legal employers are continually focusing on building cultural competency in their employees and are looking to hire people who can affirmatively demonstrate some capability in this area. Today, “a culturally sensitive lawyer understands culture is multi-faceted, and that everyone’s Worldview, conduct, perceptions, and actions are based upon a complex compilation of numerous cultural factors and experiences. A culturally sensitive lawyer is aware of the need to be self-reflective about the role culture plays in his or her interactions.”[45]

Cross-cultural competence is a career-long endeavor that requires dedication and perseverance. When law schools encourage students to develop cross-cultural skills while they are still in school, students benefit in the long-run. Developing cross-cultural skills will help students to be successful attorneys in the future by improving communication and ensuring understanding in their interactions in all cultural contexts. Failing to recognize the importance of being cross-culturally competent denies the realities of the rich cultural heritage of clients and other stakeholders in each lawyer’s professional life.

[1] Authored by Neil W. Hamilton and Jeff Maleska and originally published in Neil Hamilton, ROADMAP: THE LAW STUDENT’S GUIDE TO MEANINGFUL EMPLOYMENT (2d. ed. 2018).

[2] E-mail from Laura Witt, General Counsel, Cargill, to author (Sept. 29, 2015) (on file with the author).

[3] Susan Bryant, The Five Habits: Building Cross-Cultural Competence in Lawyers, 8 Clinical L. Rev. 33, 49 n. 53 (2001).

[4] Andrea Curcio, Teresa Ward, and Nisha Dogra, A Survey Instrument To Develop, Tailor, and Help Measure Law Student Cultural Diversity Education Learning Outcomes, 38 Nova L. Rev. 177, 232 (2014).

[5] Ritu Bhasin, Cultural Competence: an essential skills for success in an increasingly diverse world, LawPRO Magazine, Vol. 13, No. 2, 9, 10 (2014); See Mitchell Hammer, Milton Bennett, Richard Wiseman, Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory, International Journal of Intercultural Relations 421, 422 (2003) (“We will use the term ‘intercultural sensitivity’ to refer to the ability to discriminate and experience relevant cultural differences, and we will use the term ‘intercultural competence’ to mean the ability to think and act in inter-culturally appropriate ways.”); See Association of American Colleges & Universities, Intercultural Knowledge and Competence VALUE Rubric, http://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics/intercultural-knowledge (“Intercultural Knowledge and Competence is ‘a set of cognitive, affective, and behavioral skills and characteristics that support effective and appropriate interaction in a variety of cultural contexts.’”)(citation omitted).

[6] Bryant, supra note 3, at 41.

[7] WEBSTER’S THIRD NEW INTERNATIONAL DICTIONARY.

[8] Bryant, supra note 3, at 42.

[9] Susan Sample, Intercultural Competence as a Professional Skill, 26 Pac. McGeorge Global Bus. & Dev. L.J. 117, 118 (2013).

[10] Bryant, supra note 3, at 42.

[11] Bryant, supra note 3, at 42.

[12] Sample, supra note 9, at 118.

[13] See Bryant, supra note 3, at 40.

[14] Curcio, Ward, and Dogra, supra note 4, at 192.

[15] Id.

[16] J.M. Bennett, Towards Ethno-relativism: A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity, Cross-Cultural Orientation: New Conceptualizations and Applications 24-28 (R.M. Paige ed., 1986).

[17] Milton Bennett, Becoming Inter-culturally Competent, in Toward multiculturalism: A reading in multicultural education 62, 62 (Wurzel, J ed., 2004).

[18] We created this chart based on Milton Bennett’s A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity.

[19] Bennett, supra note 17, at 62. (Becoming Inter-culturally Competent . . .)

[20] Milton Bennett, A Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity, Intercultural Development Research Institute 1, 1 (rev. 2011), http://www.idrinstitute.org/page.asp?menu1=4.

[21] Bennett, supra note 16, at 3. (A Developmental Model . . .)

[22] Id. at 5.

[23] Id. at 7.

[24] Id. at 9.

[25] Id. at 11.

[26] Hammer, Bennett, Wiseman, supra note 5, at 425.

[27] Curcio, Ward, and Dogra, supra note 4, at 206 (citing William S. Howell, The Empathic Communicator 29-33 (1982)); Bryant, supra note 3, at 62-63.

[28] Id.

[29] Id.

[30] Id.

[31] Id.

[32] Id.

[33] Sample, supra note 9, at 119.

[34] Bryant, supra note 3, at 56.

[35] Id.

[36] Id.

[37] Id.

[38] Neil Hamilton, Effectiveness Requires Listening: How to Assess and Improve Listening Skills, 13 Fl. Coastal L. Rev. 145, 151 (2012).

[39] Id.

[40] Id. at 157.

[41] Bryant, supra note 3, at 73.

[42] Id. at 73-74.

[43] Id. at 62.

[44] Steve Muller, Developing Empathy: Walk a mile in someone’s shoes, Planet of Success Blog (October 4, 17:31 CT), http://www.planetofsuccess.com/blog/2011/developing-empathy-walk-a-mile-in-someone%E2%80%99s-shoes/.

[45] Curcio, Ward, and Dogra, supra note 4, at 228.

Coaching Guide

As a ROADMAP coach, you are part of a national movement to foster each student’s professional development and formation more effectively. Each law student has to grow from being a passive student, where the student just does what the professors ask, to become a pro-active lawyer owning and planning her own development including an orientation of deep care/service for the client. As a major step to facilitate each student’s growth, students read Professor Hamilton’s book, ROADMAP: THE LAW STUDENT’S GUIDE TO MEANINGFUL EMPLOYMENT (3d ed., 2023), and create a written ROADMAP plan to use the student’s remaining time in law school most effectively to achieve the student’s goals of bar passage and meaningful post-graduation employment.

The ROADMAP plan template that each student will fill out and send to you is at the end of the coaching guide (link below). The template asks the student to create a written plan to gain a breadth of experience during the student’s remaining time in law school so that the student can:

- thoughtfully begin to discern the student’s passion, motivating interests, and strengths that best fit with a geographic community of practice, a practice area and type of client, and type of employer;

- develop the student’s strengths to the next level; and

- have evidence of the student’s strengths that employers value.

Chapter 1 - Table 4

Ask Person A and ideally a second person, Person B, who know your earlier work/service well to rank your top four strengths in terms of the capacities and skills that clients and legal employers want in the context of your previous work/service with customers/persons served including work on teams.

Assessment of ________________________ (student name)

Capacities and Skills - Rank the Student’s Top Four in Order (1-4)

- Superior focus and responsiveness to the customer/persons serve

- Exceptional understanding of the context and business of the customer/persons serve

- Effective communication skills, including listening and knowing your audience

- Creative problem-solving and good professional judgment

- Ownership over continuous professional development (taking initiative) of all of the capacities and skills needed to serve well

- Teamwork and collaboration

- Strong work ethic

- Conscientiousness and attention to detail

- Grit and resilience

- Organization and management of the work (project management)

- An entrepreneurial mindset to serve customers/persons served more effectively and efficiently in

changing markets

Chapter 2 - On-line Template

Roadmap Template

Name of Student: _________________________